Remembering my Grandparents and the Holocaust

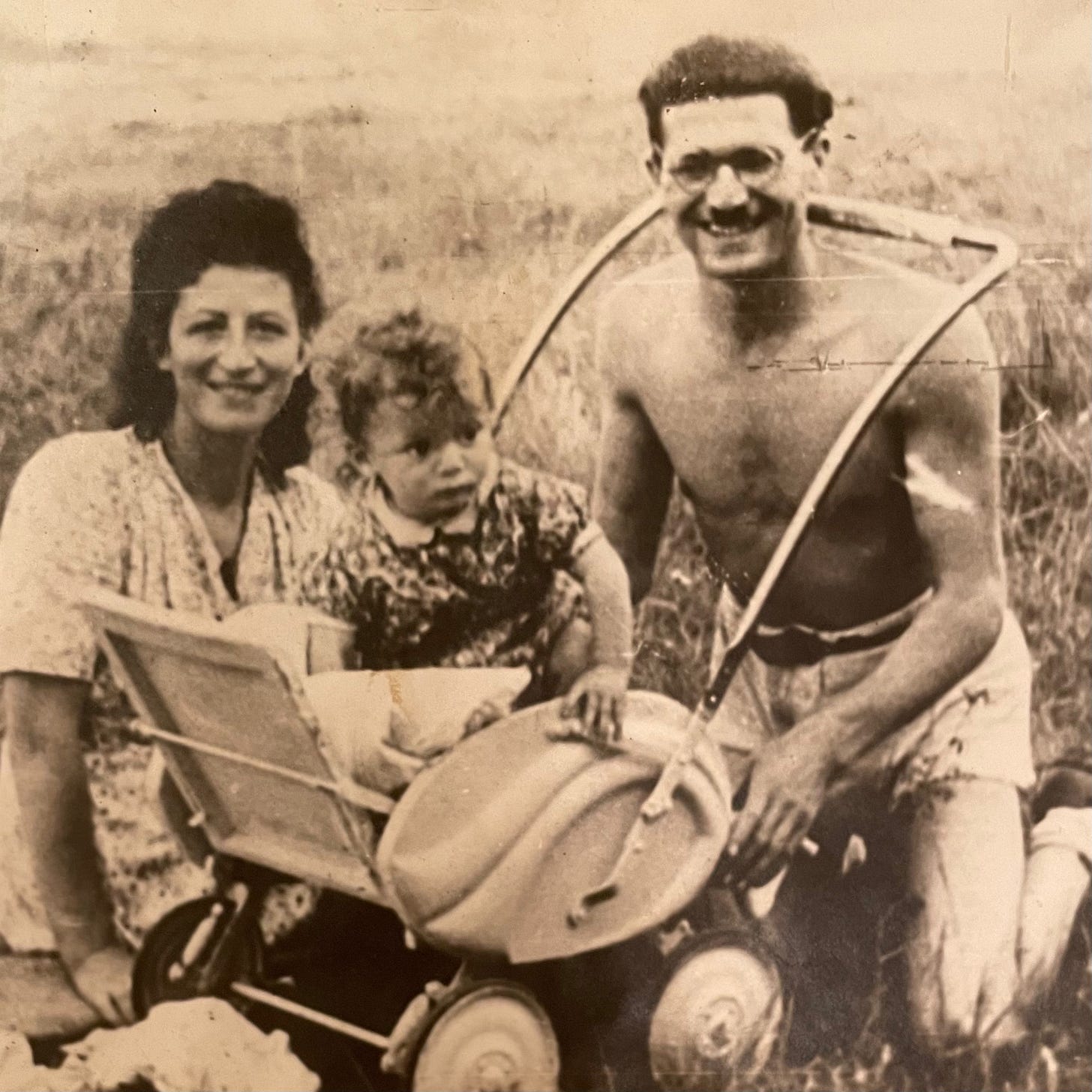

This is a picture of my Grandma Mina and my Grandpa Issak with my Uncle Joe. It was taken in a displaced persons camp in Germany, which is where they lived for four years after the Holocaust. Their parents were killed during the war along with most of their siblings (my grandmother was the only one of six children to survive, my grandfather had 12 siblings with only four surviving) and their town in Poland was completely destroyed, so there was no option to return home. Home was gone. My mother was born in the camp in 1947. It’s weird, when I think of war refugees, I think of people in faraway countries seeking shelter from conflicts I don’t really understand, but once upon a time, that was my mom.

Last night, Harlow and I were watching Cruella. There is a necklace that plays a prominent role in the movie, which is described as a family heirloom. It’s a large ruby surrounded by diamonds with a hidden key inside that unlocks a box containing family secrets. Harlow asked if we have any family heirlooms, hoping she would be the heir to some mystery pendant worth a small fortune one day, I presume. I said no. She asked why not. I shrugged and said we didn’t come from a wealthy family who would pass down such things. But when I said it, it also occurred to me that another reason we have no family heirlooms is because my mother’s side of our family had all their possessions stolen or destroyed by the Nazis. That’s not to say we had anything as valuable as Cruella’s pendant (my mother has heard conflicting stories about whether we were rich or poor before the war), but certainly there must have been at least one hidden treasure that would have grown more special to our family over time. I also blame the Holocaust for why we don’t have any family recipes passed down over generations and why we weren’t brought up with that many religious traditions.

From about 1939-1945, my grandparents were on the run, living in the forest trying to evade the Nazis. Like animals being hunted. This is how they spent part of their teenage and young adult years. I’m not sure at what point they were separated from their parents, but I know they spent most of the war on their own. Raising themselves in the woods. I don’t know if the two of them fled together or met during the war. I don’t know if they traveled alone or within a group, or if that group splintered and changed over time. I don’t know if they stayed mainly in one spot or were constantly on the move. I only know they spent the majority of those years living and hiding outdoors, eating raw potatoes for sustenance. They did not have school or organized religion or a home to decorate for the holidays or an oven to perfect freshly braided homemade challah. When my grandparents came to America and rebuilt their life here, they had to start from scratch. And they brought all the trauma of their experiences with them.

Whenever the Holocaust is discussed in school (thank god I grew up in a time and place when it was unquestionably part of the curriculum), they talk about the 6 million Jews who were killed during the war and they talk about the survivors like my grandparents. But to talk about the Holocaust in terms of death and survival ignores all of the damage in between. Many of the survivors have talked about the torture they endured while living in concentration camps, but have you ever thought about their lives after the war was over? The guilt they felt for surviving when almost everyone else they knew perished? What about the mental health of the survivors’ children?

My grandparents found their lived experiences so horrific that they never talked about any of it with their three kids. My mom and her siblings grew up knowing not to ask. Every story we’ve pieced together, we learned second hand after they passed away. With each story, we understand better why they chose to remain silent. Even writing them down now makes me feel like I am placing an undue family burden onto all of you. I’ve written about them once before. Is it too much to remind you all again?

For instance, a few years ago my mother found out that her brother Joe was not her parents’ first child. During the war, while they were on the run, they had a son. A newborn. One night, when a group of Nazi soldiers were hunting the forest for Jewish people, their baby started crying. In one version of the story told to my mother, a Nazi threw the baby in the river. In another later version, she was told the river part of the story wasn’t true. Someone covered the baby’s mouth so that their group would not be found. That person likely saved them from getting captured or killed that day, but the baby suffocated to death. I’ve asked my mom if it was possible that it was my grandmother or grandfather who covered the baby’s mouth. The truth is, she doesn’t know. They could have been with a group or they could have been alone. But it doesn’t really matter, because as mothers, we all know how hard it must have been for my grandmother to forgive herself, whether it was her doing or not.

Sometimes I wonder, when we talk about the 6 million deaths, was my grandparents’ newborn counted in that number? My mother doesn’t even know the name of the baby who would have been her oldest brother. Is there any record of his life and death? I’m also sure stories like ours are not unique.

My mother, her brother and her parents immigrated to the United States through Ellis Island in 1949. They moved to Queens, where my grandfather took a job at a small grocery store and their family lived in an adjacent apartment. My grandmother worked alongside him in the store and later became a seamstress. Is this an American success story? I’m not sure they would have seen it that way. My grandparents lived a very quiet life, working hard, keeping their heads down and trying their best to blend in. They taught their kids not to bring too much attention to themselves. My grandparents were both tortured by their past and feared history would repeat itself. Two feelings, though unspoken, which must have transferred to their children.

I never met my grandfather. He died at the age of 47 when my mother was 15. Her younger brother was five at the time. This is a common phenomenon. Many people who were considered “Holocaust survivors” actually died quite young as a result of being malnourished and living in terrible conditions for so many years. My grandmother developed multiple sclerosis and was put into a nursing home at the age of 50. She was also suffering from what would now be categorized as PTSD. Some call it “Survivor Syndrome.” There are details about her time in the home that I don’t want to share, but suffice to say, visiting her made my mother very, very sad. Grandma Mina died at the age of 55.

Last week, there was a story in the news that had Jewish people and our allies outraged. A principal in Texas said that if teachers wanted to have books about the Holocaust in their classrooms, they needed to have books with opposing views as well. I saw many people posting about it on social media, and thought, how do I even address this? It was so far out of line, I didn’t even want to acknowledge it or give it space. In a conversation about the incident with a Jewish friend, she said, “Can I just ignore this? It’s too much and I just want to live a happy life.” That’s the conundrum. Today, many modern Jewish people in America are both privileged and all too aware that at any moment, everything could be lost. We hear stories of anti-semitism every day, but my friends and I still feel safe in our NYC bubble. Don’t we deserve a little bit of willful ignorance? Or is it impossible to bury so much generational trauma?

Generational trauma is a term I learned only recently. It is defined as “trauma that gets passed down from those who directly experience an incident to subsequent generations.” When I first heard the term (in reference to another topic entirely), it sounded a little like bullshit. How could trauma be hereditary? But then when I thought about a child learning their social and emotional cues from parents who experienced trauma, it made more sense. After reading an earlier draft of this post, my mother told me that both my nursery school teacher and my sister’s told her that we didn’t trust adults, which made sense to her because she was brought up not to trust anyone around her either. She remembers feeling guilty that she had inadvertently put that on us.

I remember going to the family reunion of an ex-boyfriend many years ago. There was a school bus taking us from one venue to another. Each family member got on the bus and did a crazy song and dance down the aisle. It all looked so happy and foreign to me. “Isn’t your family Jewish?” I asked. “Yes,” he said, puzzled. I sat there, surprised by own question, trying to understand why I had asked. Then it hit me. “When did your family come to America? Before or after World War II?” The answer was before, which confirmed my suspicions. These were Jewish people whose ancestors didn’t endure the Holocaust. They were different from us. And now thinking back, I realize what I saw that day that separated us was generational trauma. I recognized it as an ability to be carefree that felt unfamiliar. To this day, I cannot imagine my family feeling the same freedom to be loud and take up space unapologetically.

I have nothing to say to the principal from Texas who thinks we need to have books with opposing views of the Holocaust. Is an opposing view a book from a Nazi sympathizer? Or one where we debate that it happened at all? Or maybe Mein Kampf? No. I don’t have time to engage with that. I want to talk to the people who would never debate the gravity of the Holocaust. I want you all to mourn the 6 million Jewish lives taken (and all the other minorities who were also targeted) and then broaden your mind to consider what kind of lives the survivors led after the war too. Think about all the newborn Jewish babies whose short lives were never tallied. And the mothers who lived with their memories. Think about the children, like my mother, who grew up in the homes of survivors, with parents who thought they should be grateful, but were still silently suffering. These kids felt the cloud of darkness, but never had it explained. Think about all the family heirlooms and recipes lost and the generational trauma that got passed down instead.

Ultimately, I believe my grandparents story to be an American success. Their survival is why my mother, my sister, myself, Mazzy, Harlow, Jack and Neve are on this earth. I hope that being vocal and telling our story, instead of keeping it hidden or shrouded in secrecy, will help our family continue to heal. And pass down a new kind of light in its place.

8 books to teach your kids about the Holocaust:

Who Was Anne Frank? (Recommended for ages 5-9)

Hidden (Recommended for ages 6-10)

When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (Recommended for ages 8-12)

Number the Stars (Recommended for ages 9-11)

White Bird: A Wonder Story (Recommended for ages 8-12)

Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl (Recommended for ages 11+)

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation (Recommended for ages 11+)

The Book Thief (Recommended for ages 12+)

Apparently is a newsletter by Ilana Wiles. If you’ve been enjoying it for free, please consider supporting it financially by upgrading your subscription! As a paid subscriber, you’ll get access to my “close friends” group on Instagram, my “Big Kid Problems Support Group” and all past TV Club discussions.

The story of your family needs to be shared repeatedly - without guilt about the "burden" it might place on others. These stories should not hide in the shadows like the survivors did for so long. In regards to the "opposing views in Texas" - I disagree that these folks should not be given the time of day - quite the opposite. These views need to be cut down loudly, swiftly and by the masses. Every single person that thinks it utter nonsense should say so on any forum available to them. When these ideas are left to themselves, they grow and become emboldened. The school official that made this statement should be publicly shamed and never allowed to work in the education system again. Period.

Thank you for writing this and all the emotional work you put in. My heart hurts for your grandparents and everything they endured to survive. There are no “sides” in this, only the truth no matter how horrible the truth is. Thank you for sharing those reading materials. Number the Stars made a huge impact on me as a child.

Also the Body Keeps the Score is a great book about generational trauma.